Emily Carr (1871 – 1945) was a Canadian artist inspired by the resilient art of First Nations (Aboriginal people) in their villages and the coastal landscape of British Columbia. Also a lively writer, “absolute frankness, simplicity and strong prose” were the language; For which he was praised. ‘Klee Week’, his first book, published in 1941, also won the Governor General’s Literary Award for Non-Fiction.

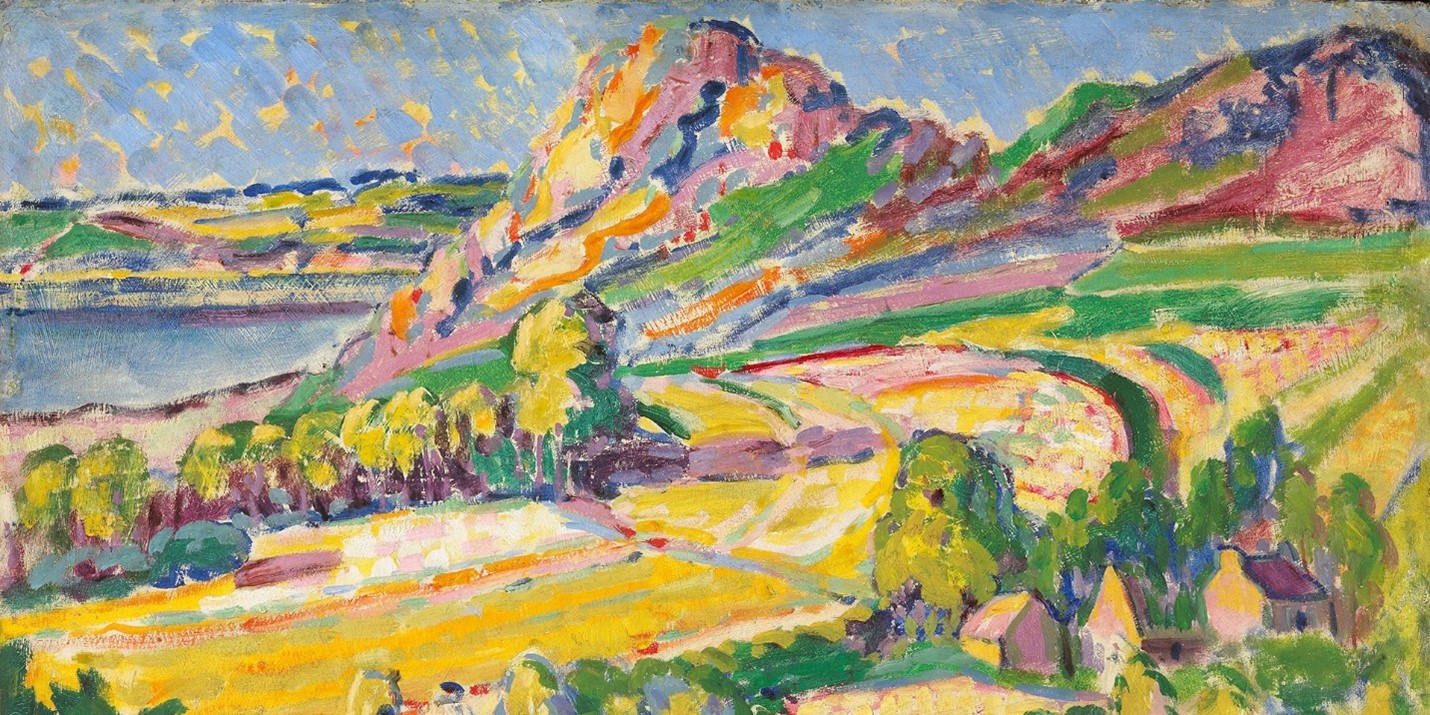

Emily was a painter and writer whose lifelong obsession was with British Columbia’s coastal environment and its indigenous peoples. Paintings spanning the Canadian west coast, Tuli’s canvases continued to express his feelings and desires on a large scale.

Early in his life his art was not well received and thus he was a little disappointed, but later achieved great success and in many ways reached the heights of greatness in recognition. Established as an icon of Canadian art. A university in British Columbia is named, “Emily Carr University of Art and Design”.

In 1912, Carr went on a six-week painting trip to fifteen First Nations villages along the coast of British Columbia. In 1927 Carr was invited to participate in the Canadian West Coast Art Exhibition in the capital, Ottawa. The exhibition included thirty-one of his paintings. He had arrived earlier for the inauguration. Before his death in 1945, the Vancouver and Toronto artist met members of the Group of Seven, one of whom remained in touch through a lifelong correspondence with Lorraine Harris, one of the most famous.

Since then the best period of his career began. He painted with aboriginal subjects until 1931, then adopted British Columbia’s rainforests, aboriginal art and maritime coastal skies as his main subjects. When he suffered a heart attack in 1937, he devoted most of his time to writing. Numerous galleries and museums, including the National Gallery of Canada, have exhibited or still have Emily Carr’s work. Emily Carr’s art has sold at auction multiple times for $3.2 million or more, depending on the size and medium of the artwork.

How did Emily Carr change the world of art?

In the 1930s, Carr rearranged existing First Nations iconography and built on his own imaginative repertoire, creating an image for the West Coast that evoked political, social, cultural, and environmental issues in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Even his books are probably the best biographies written in Canada in the literary sense. Carr was a natural storyteller whose stories were enriched by an artist’s eye for narrative and felt for the failings of humanity — featuring seven of his books so popular they were critically acclaimed. However, many books he could not publish during his lifetime because he became too committed to painting in his late life, but all were published after his death.

In Emily Carr’s art, pictorial style and progressive thematic concerns are evident. Despite the sometimes patronizing tone of his writing, Carr is deservedly celebrated for his prescient solidarity with indigenous peoples in a time of relentless government-sanctioned oppression. He also realized the implications of capitalism’s view of landscape as commodity. Protested against the increasingly widespread practice of logging in his home province of British Columbia.

Carr was born into a very conservative English family in Victoria in 1871; Year British Columbia joined Canada. His father, Richard Carr, was an ostentatious wealthy businessman, living in Victoria who thought of himself as English rather than Canadian. Richard did not know or understand the climate in which he lived. He also tried to raise the family in strict English tradition and religious orthodoxy. Wanted to teach the daughters to grow up in the Presbyterian tradition, with Sunday morning prayers and evening Bible reading. In contrast, Emily Carr struggled to be independent from her family from a young age.

From a young age, he became fond of local British Columbia. The question arose in his mind when and where did the history of Canada begin?

Maps and textbooks in school history show the arrival of Europeans on Canada’s east coast—Vikings, French explorers, Portuguese and Spanish fishermen, English and Scottish fur traders, Irish refugees, etc.

The first group of humans to appear in North America were the Clovis people, who arrived about fifteen thousand years ago via a land bridge from Siberia to Alaska and present-day Yukon. Then it spread to this continent from the north. By the time Europeans arrived in the south and began occupying the land and naming the colonies, hundreds of thousands of people were already living in the areas from sea to sea. Without the help of these indigenous inhabitants, many Europeans would not have survived the harsh climate and brutal geography.

But the Eurocentric view of Canadian history has never let up on reality. The language, economy, and lifestyle of West Coast peoples such as the Haida, Kwakwakwa, Nisga’a, and Tlingit, which had survived for generations before their lands were taken over for the British Empire, were not taken into account. British immigrants Until recently, the province and its indigenous cultures were marginalized in the way we told our stories.

When did Emily Carr decide to become an artist and why was that West Coast depression so important to her? The book of small (The book of Small) and the book of growing pains (Growing Pains), childhood memoirs written half a century later or several biographies of his family, and expressed his ideas in Victoria about art. What is clear is that Carr was a determined, restless little girl with a strong visual sense and a great curiosity about the natural world. One with a square chin, a stubborn outlook who preferred to portray animals, flowers, nature and even indigenous people and their culture more than people. Disagreement with his sisters over his own plans, his relationship with his father was always difficult, so to speak, contradictory in outlook; However, Carr wanted to move forward with peace of mind.

She lost both her parents when she was a teenager, her elder sister ‘Edit’ took over the responsibility of the family.

Whom Emily calls Didi, her views are as conservative as her father’s. Carr has to overcome family bitterness and resentment.

He decided to go to England and France to study art, earning money himself.

Artistic instincts inspired by nature, which he probably acquired refined in England by studying art there. France mastered the characteristics of Arte Rong.

Sister ‘Alice’ was the only one in the family who loved art and often accompanied Emily on her journeys to work. In 1907, Dubon traveled by steamer to Sitka, Alaska, on the coast, where he discovered a new indigenous art form of totem pole carvings. These works impressed Carr, depicting many totem poles in village locations.

This is how Carr, speaking of his own experiences, sought to explain the culture he painted. “I glorify our wonderful West, and I hope to leave behind some of its first ancient grandeurs, as heritage to us Canadians. As ancient Britain’s feats are to the English. And in only a few years these will pass forever into the silent void. Before they are forever past.” I will consolidate my collections.”

Despite all the conventional upbringing, Carr showed a great respect for indigenous traditions and culture. Especially when compared to the brutal and ugly racism of government policies and popular culture that portrays Aboriginal people as less than human.

It was Lauren Harris (of the Toronto Art Group of Seven) who inspired Carr to embark on his greatest and most distinctive phase. In a 1931 letter he suggested to her that underlying his strong feelings for Aboriginal art reflected his own deep response to the West Coast landscape. The totem pole is a work of art in its own right and is very difficult to use in another form of art.

‘Clee Week’ (1941) is a memoir by Emily Carr, consisting of a collection of her literary publications. It was a stimulating task; which describes in detail the influence of the indigenous peoples and culture of the Northwest Coast on Carr. The name Kli Wik (“the laughing one”) was given to him by the Nu-chah-nulth (Nootka) people. The book won the Governor General of Canada’s Literary Award for Non-Fiction in 1941 and has been translated into many languages.

Even as a child growing up in Victoria, Emily was ‘the opposite’. She rebelled against attitudes that wanted to confine her to ladylike Sunday paintings. As a teenager he escaped the strict authority of his family by leaving home to study art in San Francisco. Then as a young woman, defying conventional norms, she chose art over marriage as well. When a lover comes with a marriage proposal, he rejects it.

Emily meets D’Sonoqua, the wild woman of the forest, in an isolated native village on the coast. Deeply influenced by his encounter with this mythical figure, he felt that his canvas had a mission to preserve the endangered heritage of local villages and totem poles. He made several trips to the Northwest Coast with only a sketch-pad and a dog for companionship. He rode freighters, fishing boats, and canoes—anyone who could take him near the totems. For many unhappy years her art was not accepted, and Emily made a living as a land lady. He then met seven artists (the Group of Seven) in Toronto, who created a new style of Canadian painting for the new country. No longer isolated, at age 56 Emily began an intense and productive period of painting and writing.

He went beyond the totem pole into the forest to explore the spiritual aspects of his beloved landscape. Listening to her own inner voice, Emily Carr created an art unique to Western Canada.

Carr’s vividly poetic prose contains vivid expressions of totems, abandoned villages, Northwest Coast aboriginal culture, broken-English dialogue, and landscapes. It never falls into nostalgic sentimentality, sociology or romance. His writing inevitably invites analogy with his painting. Carr’s gifts with words are no less exceptional than with images. He perceives with a deeply sympathetic eye and achieves a remarkable purity through the careful translation of his images into language.

Today Emily’s vision is recognized as richer and more complex than that of her contemporaries. He gave Canadians a greater sense of our relationship, past and present.

Emily Carr left precious gifts to the world through paintings and books; All this is our heritage in Canada.