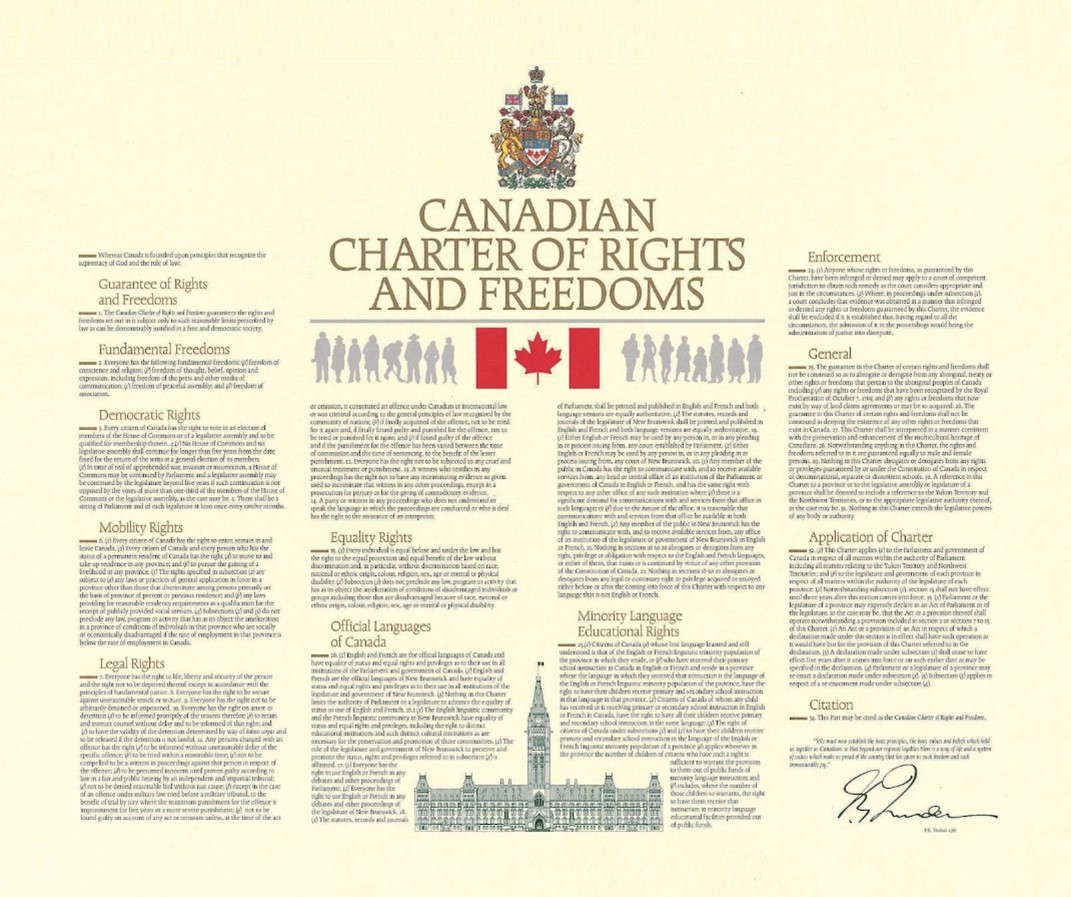

The most prominent and recognized part of the Canadian Constitution is the ‘Charter of Rights and Freedoms’ or more commonly the Charter. This Charter guarantees the rights of any individual subject to certain limitations in the supreme law of the land. Since its enactment in 1982, Canada has undergone a social and legal revolution. It also extends to legal restrictions on the rights of minorities and criminal defendants. Reformed and moderated the nature and cost of criminal investigations and prosecutions. It has even brought the will of Parliament and the Legislature under judicial scrutiny. Although this is still a matter of ongoing debate today.

Background:

Rights and freedoms were somewhat protected by various laws in Canada before the Charter was established. Canada still included a Bill of Rights, from the early 1960s. Although important, none of these laws were part of the Constitution. As a result, charters lacked dominance and permanence. Moreover, the Bill of Rights applied only to federal, not provincial, laws.

A remarkable effort:

The government of Pierre Elliott Trudeau began the process of popularizing Canada’s constitution in the early 1980s — even attempting to make the constitution independent of the British Parliament. The Trudeau government incorporated a new Charter of Rights and Freedoms into the Constitution. Between 1981 and 1982, the constitutional debate over it was detailed. There were concerns about how much power the Charter would place in the hands of courts and judges of legal interpretation. There were also many questions about how corrections could be made after launch. Provincial leaders feared that the Charter would limit the right of provincial governments to make their own appropriate laws!

Trudeau’s Justice Minister Jean Chrétien (later Prime Minister) did the hard work of drafting and negotiating the Charter. Chrétien was assisted by two provincial attorneys-general, Roy Romano of Saskatchewan (later premier) and Roy McMurtry of Ontario. Ontario Premier Bill Davis also helped revive the charter.

At the time, Quebec Premier René Lévesque was not particularly concerned about charters. Because in 1975, Quebec passed its own Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms. These took precedence over other provincial laws although were not incorporated into the Canadian Constitution. Lévesque was initially strongly opposed to any new federal constitutional arrangement. particularly those that did not recognize Quebec’s traditional constitutional veto power. He later agreed to surrender the veto in exchange for a constitutional treaty. In order to give priority to the provincial rights of Quebec. Lévesque always regarded the Charter as a federal authoritarian constitution.

The premiers of the other provinces, led by Chrétien and Romano, agreed to the new proposal, without Lévesque’s approval. Because, Romano explained, “the additional amendments or changes requested by the province of Quebec, in our opinion, would be unclear or delayed if the constitutional process were stalled.”

Lévesque and his allies strongly objected to the way the constitutional treaties had been negotiated in their absence. They considered it a stab at Quebec. “What they did this morning is indescribable,” Levesque said. “Everybody needs to think through and understand, and the consequences of what happens next can be incalculable.” As a final step, the Quebec government never signed the Constitution Act-1982 or formally ratified the Charter. However, as the Constitution was determined by the Supreme Court of Canada, the Charter was legally binding without the approval of any provinces. All Quebec legislation was therefore required to respect the Canadian Charter. The Quebec Charter was also considered as constitutional law.

It is worth noting here that Lévesque has been a leader fighting for the sovereignty of Quebec from the beginning of his political career and for that purpose he formed a party called Parti Quebecois in 1968. His party won the Quebec vote in 1976 and Lévesque became premier.

Ottawa has an amendment formula for charters between the federal government and the provinces. Any amendment is possible with the consent of Parliament and the legislatures of the seven provinces representing at least 50 percent of Canada’s population. The Charter has been amended twice since its entry into force.

After months of passionate public debate, the Charter came into effect in 1982, as the Constitution Act. Queen Elizabeth II signed the Canada Act-Governing Act 1982 into law on April 17 in Ottawa.

Where the certificate applies:

The Charter protects Canadians across national borders. It also protects minorities among parliamentary majorities. This applies to all Canadian citizens or newcomers. However, some rights apply only to citizens, such as the right to vote and the right to enter and leave the country. Its language is decidedly generic, which is a reason critics fear. This gives judges too much interpretive power.

The main rights and freedoms protected in the Charter are freedom of expression; the right to a democratic government; the right to live and work anywhere in Canada; legal rights of persons accused of crimes; Aboriginal Rights; The right to equality in all areas, including gender equality; The right to use the official language of Canada and the right of French or English minorities to be educated in their own language.

Article one (1) of the Charter empowers the government to restrict certain rights and freedoms as necessary. As long as those limits “seem substantially justified in a free and democratic society.” There have been numerous court cases to uphold such limits. For example, in the 1992 Butler case, the Supreme Court of Canada held that a law dealing with pornography is a reasonable restriction on the right to free expression because it protects society from harm in other ways.

Special Clause:

Article 33 of the Charter empowers the Government to make exemptions in certain cases from certain clauses by law. But not from democratic mobility or language rights. The federal government, however, never enforced this clause. It has been used several times by various provincial governments to override charter rights.

Between 1982 and 1985, the Parti Québécois invoked Article 33 in every piece of charter legislation passed by the National Assembly. This was done in defiance of the Charter, but did not violate any rights. Furthermore, in 1988 the Quebec Liberal Party invoked Article 33 to pass Bill 178, requiring restrictions on the use of English-language signs and advertisements.

In 1986, the Progressive Conservative government of Saskatchewan Premier Grant Devine invoked section 33 in the ‘back-to-work’ law. However, the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal ruled that the Charter rights were violated. After the Supreme Court accepted the government’s appeal against the judgment of the lower court, there was no need to invoke Article 33 of the Premier Divine.

Ralph Klein’s Progressive Conservative government in Alberta used Section 33 to pass a law against same-sex marriage in 2000. However, the Supreme Court ruled in 2004 that marriage laws are the jurisdiction of the federal government; It legalized same-sex marriage in all provinces and territories in 2005.

In 2017, Brad Wall’s Saskatchewan Party also invoked Section 33 to override a court ruling that denied provincial funding to non-Catholic students attending Catholic schools.

In 2018, Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government used this clause in Ontario. The Ford government passed legislation to reduce the size of Toronto’s municipal council. The law was struck down by an Ontario Superior Court judge for violating charter rights. The Ford government passed the legislation after the Ontario Court of Appeal stayed the Superior Court’s decision.

In June 2019, the Coalition Avenue Quebec (CAQ) government led by Francois Legault passed Bill 21, (Secularism Bill). The law prohibits employees in all government jobs, such as teachers, police, judges, etc., from wearing religious symbols while on duty. Legault’s government invoked Article 33’s out-of-bounds order to violate Charter rights. The law sparked protests and controversy, and was criticized by many as a form of discrimination.

Toronto, Canada